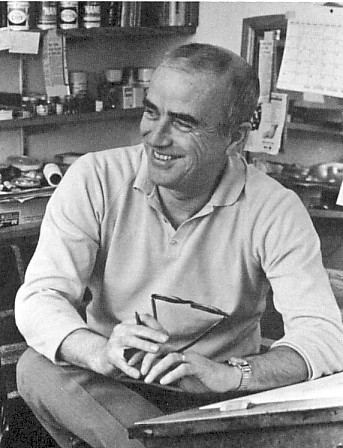

Doug Wright (1917-1983)

Douglas Austin Wright was the critically acclaimed author of Doug Wright’s Family, arguably the most widely recognized Canadian comic strip of the mid-twentieth century. Hailed for his unparalleled draftsmanship and his touching, compact narratives, Wright, alongside Charles M. Schulz and George Herriman, is one of only a handful of truly seminal twentieth century cartoonists.

Born in England, Wright immigrated to Canada in his teens in 1938. He was a proud Canadian citizen, a fact often reflected in the modest, suburban Ontario life depicted in his most famous strips. His cartooning career really began when he landed a job as editorial cartoonist for the Montreal Standard. In 1948 he took over the reins of Jimmy Frise’s Birdseye Center, retitled Juniper Junction. Signing the strip “DAW”, he continued with it until its end in September, 1968. Wright created Nipper, a mostly silent comic strip, for the Standard in 1949.

Wright excelled at the depiction of childhood and the daily charms and frustrations of late-20th Century domestic life. A skilled draftsman, his fluid cartoon figures whirled through meticulously-rendered backgrounds and suburban landscapes.

Nipper was rechristened Doug Wright’s Family in 1967 when Wright moved from Montreal to Ontario. The strip enjoyed a long run, entertaining a generation of Canadians on a weekly basis until Wright ended it in 1980. Wright created a number of other strips and attempted to syndicate them, with some limited success, in addition to regular work in illustration and drawing syndicated editorial cartoons for the Montreal Standard and later the Hamilton Spectator. 2005 saw the inauguration of the Doug Wright Awards, honouring special achievements in Canadian cartooning.

Below is an essay about Wright by Brad Mackay, a writer and Director of The Doug Wright Awards, that was published in 2015 in the anthology book Drawn & Quarterly: Twenty-Five Years of Contemporary Cartooning, Comics, and Graphic Novels.

Drawing from Real Life: An Appreciation of Doug Wright

By Brad Mackay

Like all of us Doug Wright played a number of roles in his life: loving husband, harried father, gifted draftsman, disgruntled taxpayer, devoted car-racing fan, maniacal model builder, and proud World War II veteran. But I think Wright would agree when I say that two words best sum up his time on earth: working cartoonist.

Much like Charles Schulz, to whom he was often compared, Wright thrived on routine. After rising every day at around 8:00 a.m., he ate a spare breakfast of toast and jam, drank a cup of tea, then climbed the stairs to his home studio on Rankin Drive in Burlington, Ontario, where he spent the next ten hours or so drawing one of his many comic strip features, which totaled seven at the peak of his career. This was in addition to his freelance illustration gigs, which he worked on after he downed his five o’clock rye-and-water and had dinner with his wife and three kids.

And while all of his strips held their appeal, we probably would not be discussing Wright today if it weren’t for Doug Wright’s Family, which ran weekly in newspapers and magazines from 1949 to 1980. First appearing on March 12, 1949 in the back pages of the Montreal Standard, the untitled black-and-white strip about a mayhem magnet of a toddler was an instant hit with readers. The paper quickly responded with a readers’ contest to name the suddenly popular brat. There were dozens of entries, but “Nipper” won out (much like Schulz, Wright hated the name his editor saddled him with) and the strip would use it as its title for the next eighteen years. That is until Wright moved the strip to a new paper and copyright issues forced him to change it to the more literal Doug Wright’s Family. He chafed at that name too, but it couldn’t have been more perfect.

By the 1960s the strip was a literal reflection of Wright’s growing family life. When he started the strip he was a bachelor, with zero insight into family life. By 1960 he was married (to Phyllis Wright) and had three boys, aged one, four, and seven. The strip, once a simplistic gag-a-week, had grown along with him. The mom and dad were dead ringers for Phyllis and Doug, and the strip added a second boy shortly after their second son was born.

Without realizing it Wright had created a comic-strip simulacrum of 1960s family life. The strips that weren’t based on his own experiences were usually based on another family he knew, which rooted the strip in a recognizable domestic reality—one complete with agitated moms in hair curlers and fuming, frazzled dads beset by kids who could switch from engines of bedlam one minute to refuges of pure joy the next. This was—and is—family life for most of us, and people came to appreciate Wright’s unsanitized domestic snapshots.

For all of the comparisons to Charles Schulz’s enormously popular Peanuts (which Wright privately bristled at), it’s not fair to compare the two. As a child of the 1970s I loved Peanuts, but even I didn’t think of Charlie Brown and the rest of his gang as actual kids. To me Schulz’s universe was a stage for complex anxieties played out by children understudying their adult counterparts. Peanuts is an undeniable masterpiece but its children were funny-paper orphans. They tormented the hell out of each other, but never had a mom or dad to go to when they got hurt.

That’s why even though I loved Peanuts as a reader, as a kid I identified with Doug Wright’s Family. I wasn’t alone. Wright’s work inspired at least two generations of cartoonists including Lynn Johnston (who credits Wright as one of the two reasons she became an artist), Chester Brown (whose first published work at the age of 11 was a Doug Wright’s Family rip-off) and Seth, whose reverence for Wright has been channeled into four books, and an annual comics awards show named in Wright’s honour.

It’s not a stretch to say that Wright was unconsciously creating a form of comic-strip vérité. Wright’s bald-headed boys acted like kids—not adults—and they had parents who loved them and were there for them. Like hundreds of other Canadians of my generation, I saw myself in Doug Wright’s Family, and now that I have three kids of my own, I still do.

Brad Mackay is a writer, comics journalist and co-founder of the Doug Wright Awards. His writing has appeared in the Globe and Mail, Toronto Star, Ottawa Citizen, CBC, Toronto Life, Quill & Quire, and other places. www.bradmackay.com