Seth’s Giants of the North speech for James Simpkins

Posted on 17. May, 2016 by Brad Mackay in ceremony, News

This speech, prepared for the occasion of James Simpkins being inducted into the Giants of the North Hall of Fame, was delivered by the cartoonist Seth at the 12th annual Doug Wright Awards for Canadian Cartooning, on May 14, 2016, as part of the Toronto Comics Arts Festival.You can also download a transcript of the speech here DWA 2016_Simpkins Seth Giants speech or, listen to the audio below.

This speech, prepared for the occasion of James Simpkins being inducted into the Giants of the North Hall of Fame, was delivered by the cartoonist Seth at the 12th annual Doug Wright Awards for Canadian Cartooning, on May 14, 2016, as part of the Toronto Comics Arts Festival.You can also download a transcript of the speech here DWA 2016_Simpkins Seth Giants speech or, listen to the audio below.

Time erases just about everyone from the marketplace of the culture. Even big Hollywood stars of the past like Tyrone Power or Jean Arthur, are probably unrecognizable names to most young people today. They were practically just names to me when I was a child. In fact, back then silent stars like Wallace Beery or Marie Dressler were people I had never heard of despite the fact that they were once world-famous.

So it is no surprise that in the little world of Canadian cartooning time has erased the names of important artists like Jimmie Frise, George Feyer, or James Simpkins. But that doesn’t erase what they left behind. Even if the big world of the marketplace has moved on to other things their work still exists, and we can look back at it, admire it, learn from it, and try to understand it. That is the purpose of the Giants of the North Hall of Fame: to remind us that everything of value isn’t just confined to the moment we currently occupy. And to allow us to peer back and honour the memory of those who helped build the Canadian cartooning art form.

So it is no surprise that in the little world of Canadian cartooning time has erased the names of important artists like Jimmie Frise, George Feyer, or James Simpkins. But that doesn’t erase what they left behind. Even if the big world of the marketplace has moved on to other things their work still exists, and we can look back at it, admire it, learn from it, and try to understand it. That is the purpose of the Giants of the North Hall of Fame: to remind us that everything of value isn’t just confined to the moment we currently occupy. And to allow us to peer back and honour the memory of those who helped build the Canadian cartooning art form.

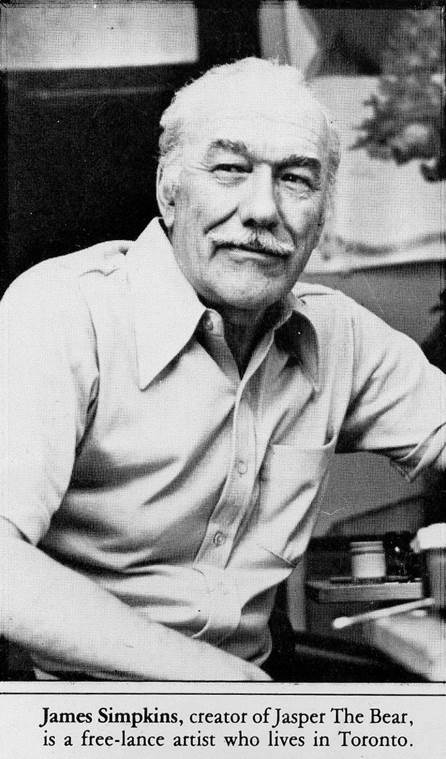

Tonight we honour Mr. James Simpkins, born in 1910 and died in 2004. I have been waiting a long time for this particular Giants of the North induction. I’ve wanted him in the Hall of fame since we first established it 11 years ago. The only thing that has delayed his entry has been our desire to honour living cartoonists first. But James Simpkins has always been a personal favourite of mine. When he died in 2004 the National Post asked me to write an obituary for him. What follows is an altered form of that text.

I think it is safe to say that Jasper the bear was Canada’s most recognizable cartoon character of the 20th century. Just how well-known he is today is debatable. Certainly if you are over 50 years old or live near Jasper Park then you will instantly know his face. However I suspect he is fading away from younger generations. That’s a shame really. He was a character with a lot of quiet charm about him much like his creator, James Simpkins.

Simpkins was a part of a small group of cartoonists, mostly starting out in the 1950’s, who helped define the young pop-culture of Canada. Peter Whalley, Doug Wright, Len Norris, Walter Ball, Jimmy Frise—these names are fading away as their work grows dusty on the shelves of neglected second-hand bookstore humour sections. Canada’s home-grown media was small in those days and our pop-culture was still fresh and relatively undefined. Looking back you can see that those involved made a concerted effort to create a Canadian pop-culture that was separate and identifiable from that of Mother Britain or our American neighbours to the south.

The clichéd images of Canada that we roll our eyes at today were just then taking concrete shape during the decades of the 1930’s to the 60’s. It was in Simpkins’ generation that all those Mounties, beavers, lumberjacks and gap-toothed hockey players were being converted from folksy images into funny streamlined archetypes, with the help of the modern gag-cartoon.

The clichéd images of Canada that we roll our eyes at today were just then taking concrete shape during the decades of the 1930’s to the 60’s. It was in Simpkins’ generation that all those Mounties, beavers, lumberjacks and gap-toothed hockey players were being converted from folksy images into funny streamlined archetypes, with the help of the modern gag-cartoon.

Jasper himself was a part of this phenomenon—created to be a Canadian image but with a modern sensibility meant to avoid the saccharine sweetness of previous kiddie-friendly animal characters. He was cheeky, self-possessed and something of an absurd con-man as well. He first appeared in the pages of Maclean’s magazine on November 15, 1948 and ran weekly for more than 30 years. In short order he became a familiar face on the Canadian landscape and was popular enough to generate warehouses full of merchandise: cups, plates, figures, inflatables, colouring books, dolls, pins, banks, etc. etc. You can still purchase a zippo lighter with his image on it today. There were also several popular book collections of his cartoons and a newspaper comic strip that ran for a few years in the late 60’s.

People forget just how popular gag-cartoons were back before the 1970’s. We only see them in The New Yorker today, but back then every magazine had them. And there were thousands of magazines across North America. Simpkins’ was a freelance gag-cartoonist, which that meant he worked wherever there was work, and in the days before Federal Express, fax machines, scanners or email this meant he was mostly tied to the Canadian print media, primarily in Toronto. His cartoons appeared in Maclean’s, Weekend, The Standard, The Family Herald, The Montrealer; just about any old Canadian magazine you can dig up.

He was obviously prolific, having produced a large body of cartoon work. It was undoubtedly hard work too — you try coming up with 30 years of gags about bears. Canada was a pretty small market then and he must have pushed himself hard to make a good living for his wife and five children, but looking at the drawings themselves he obviously took real pleasure in the work. The cartoons are always wonderfully rendered, well-designed, full of life and charm and clearly show the signs of a hand that enjoyed drawing them.

The gag cartoon was a strange and subtle little form. Not as easy as it looks and difficult to master. Everything depended on a single drawing and a single line of text. A small frozen incident, sketched out, at which the viewer gazes, often perplexed, for just a second, then the eyes dart down, take in that explaining line of dialogue, and all is clear. All this in the hope of conjuring a tiny little humorous spark in the reader’s mind that will be generally forgotten moments later. The whole production dare not feel laboured. The drawing had to breezy and pleasant to look at. The humour— quick, matter of fact, off-the-cuff. If it smacked of effort or made you think too much about it it failed. And you had produce hundreds of these little visual puzzles every year to make a living. All just for the reader’s momentary division. Like I said earlier, it was hard work.

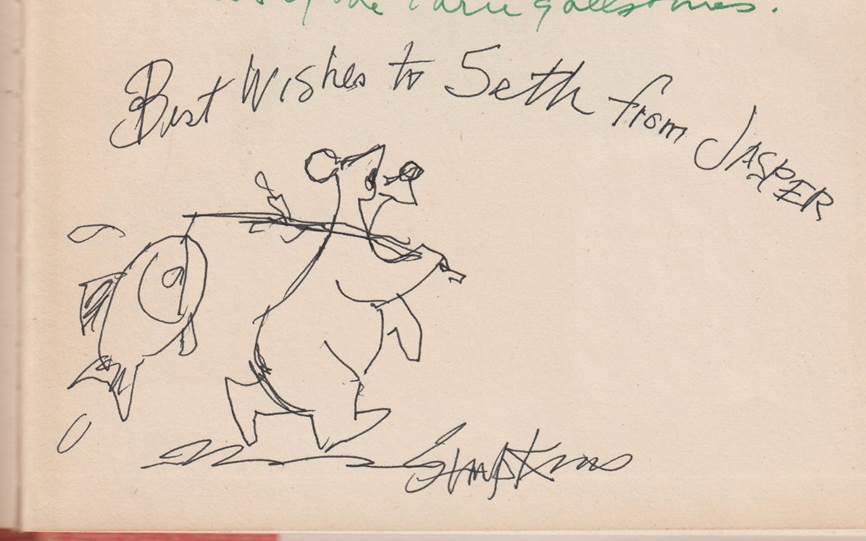

I first came across Simpkins cartoons when I was a child, in the pages of Canadian Boy magazine—the house organ of the Boy Scouts of Canada. He drew a cute little beaver cartoon in there titled Chopper that was a real favourite of mine. I copied those drawings of his over and over again and this was a big part of my early education as a cartoonist. I’ve spend many years since tracking down those old magazines so I could once again study those Choppers as an adult. They are extremely sweet cartoons—part of another era.

I only met Simpkins a couple of times, the last being when writer Brad Mackay and I went out to visit him at his retirement home in Dundas, Ontario. We were doing some research for a book on Canadian cartoonists of the past and we wanted to ask him a few questions. As soon as we arrived it was apparent we were in the right place. The elevator and his entire floor were papered with Xeroxes of his cartoons. What I didn’t know then was that he photocopying his old cartoons, carefully colouring the copies, and posting them up around the building.

Upon entering his room we immediately saw that it was similarly wall-papered with cartoons and photos. The souvenirs of a career as a cartoonist were everywhere: a large photo of Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau hugging a “life”-sized Jasper dominated the room. In the corner was a drawing table that was clearly still being used, mostly to colour those photocopies I guessed. For a man in his 90s he was in wonderful shape—trim, well-dressed and obviously still very able.

After some brief preliminaries I launched into my questions. It didn’t take long for me to realize that his memory was not up to the task. After a few more attempts to pry out some answers I put aside my 87 type questions and decided to simply enjoy the opportunity to sit and talk with him. He was exceptionally charming that day; he never once stopped smiling except perhaps for the times his memory failed him. I asked him when he had retired and like a true freelancer, he answered, “Oh, I haven’t retired—I’m still shopping a few things around”.

Just before we left he reached up and pulled down an object from a high shelf. “Look what I found for my grandchild” he said. It was a large golden plastic crown, and after holding it out for us to admire he gently placed it on his own head, and with a broad grin on his face he flipped a little switch on the side of the crown and, unexpectedly, tinny electronic music began to play.

That is how I will always remember James Simpkins.

As we walked out to the car afterward, I thought about the paths in life and how they take you to strange places. I thought of myself as a child, copying out those Chopper cartoons at the kitchen table and how they had led me to the door of this old man. He had no idea, I’m sure, that when he drew those ephemeral drawings back in the early 60s that more than 30 years later someone would still be thinking about them.

And I am still thinking about them today. Ten years after that obituary was written. In fact, a few years ago, when I wrote my imaginary comics history The Great Northern Brotherhood of Canadian Cartoonists, I could not resist casting Simpkins as the long standing-president of the made-up club. I didn’t draw him in the book, but I should have and I should put a crown on him. Instead today, I have the pleasure of inducting him into The Giants of the North Hall of Fame for Canadian Cartooning.

I’d like to welcome his grandson Kevin Boyle to accept this medal in his name.

One Response to “Seth’s Giants of the North speech for James Simpkins”